The Beauty of Stop-Motion Animation with Bottle George Director Daisuke ‘Dice’ Tsutsumi

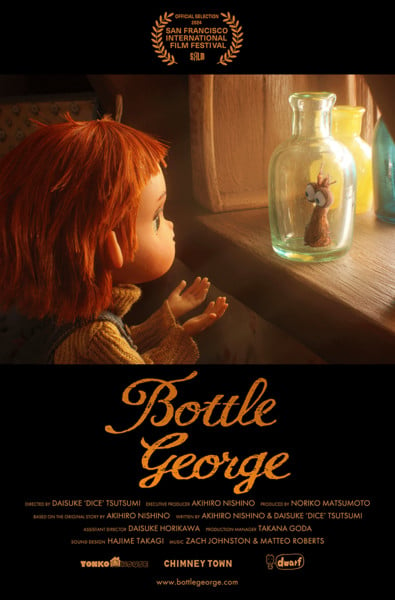

Director Daisuke “Dice” Tsutsumi contributed to films like Toy Story 3 and Monsters University while simultaneously crafting what became his Academy Award-nominated animated short film, The Dam Keeper. His latest short film, Bottle George, is an exploration of alcoholism through a child-friendly lens and follows the young girl Chako as she deals with her father’s addiction and cares for the best version of himself while he’s trapped in a bottle. The palatability of this heavier subject is largely thanks to the work of dwarf studio, the production team behind Pokémon Concierge, who beautifully realize a world that’s filled with as much wonderment as it is woe.

In this interview, Daisuke Tsutsumi discusses how he left the traditional studio system to start his animation studio, Tonko House. He also speaks about how he partnered with comedian and children’s book author Akihiro Nishino to hone Nishino’s vision for Bottle George. The conversation then ends with Daisuke discussing how Hayao Miyazaki, his uncle by marriage, has influenced his work and how he thinks the more tactile nature of stop-motion animation will lead to it becoming more prominent and important as AI technology has a growing presence in the medium of animation.

What inspired you to pursue film production? Have you always wanted to work in film production?

DAISUKE TSUTSUMI: No, it was a long journey for me. I migrated to the United States when I was 18 in college. I didn’t speak a word of English, and that forced me to take classes in a college that didn’t require English, one of them being an art course.

That’s how I got into art, which was the start of my career as an artist. Until then, I was into sports and played baseball all my life in Japan. By the time I graduated, I realized that animation was one of the possibilities for my future career.

That is great to know. Moving a little ahead in your career, what motivated you to leave Pixar and strike it out on your own as a director, as a showrunner?

TSUTSUMI: There are a lot of layers to that. To give you the quick version, we made The Dam Keeper while we were at Pixar. I made The Dam Keeper with my co-director, Robert Kondo, who’s my partner at our studio, Tonko House. Both of us at the time were very content with our careers. We had a very good job, Pixar treated us well, and we were a part of huge, international, box office successful movies. But we were looking for purpose in our lives at the time. We were in our mid-thirties, and, you know, we felt like we needed to understand why we’re making movies in general.

And in trying to answer that question, we did our independent short film, The Dam Keeper, while we’re still at Pixar: on the weekends, at night, in the morning, and really any off hours we had. Through that experience, we realized how much we didn’t actually know about making movies, even though we had been working in the film industry for a long time! We realized there’s so much more to the filmmaking process and, more importantly, we wanted to connect with our audience more directly.

We felt like we had to leave Pixar to do that. While being at Pixar was incredible, we weren’t the ones sort of facing and talking to the audience in our positions as art directors. And that’s how we branched out from Pixar and started the Tonko House studio.

There’s a really strong, I think “team mentality” is the polite way to put it, when working at a major studio like that. You have to be all in on the project, company, and culture.

TSUTSUMI: Yeah, and there’s nothing wrong with that, right? It’s just that, at that time in our careers, we needed to start questioning, “How could we contribute to the world and our children?” My child was born while we worked on The Dam Keeper. He was just about one year old when we finished it. And that made me question, “What could I do to make a difference in the world for him?” And I felt like I had to leave Pixar to be able to do something, to make something more influential for my son.

Speaking of The Dam Keeper, I watched it before this interview. And now that I’ve also seen Bottle George, I’m noticing a trend in your work where the aesthetics of children’s media are used to tell stories with heavier themes. How do you think this continues in Bottle George? What about this incongruity appeals to you? How do you balance the sense of childlike wonder with the harsh realities of life?

TSUTSUMI: Yeah…that’s a good question [laughs].

It’s always a difficult challenge because life is one thing we said when we started Tonko House. We said, “Let’s just have honesty in our work.” Something that we can just stand by and say, “This is the life we know; this is the world we know.” And the world is not always a soft and comforting place. And I genuinely believe Pixar, especially in the old days, but even today, is one of the few major studios that’s pursuing that kind of media.

Maybe their balance is slightly different from ours, but I do know that they pursue that very sincerely. We definitely come from that camp where whatever story we tell has to be honest. It has to be something that we know and feel with conviction, as opposed to something that we think an audience will like but that we don’t necessarily believe in. We’re never going to do that. That’s what we said when we started Tonko House.

Showing heavier subjects in our work is being true to that idea because we’ve all experienced uncomfortable things in our lives today. But I always feel like there’s hope. I always feel like there is something more powerful. Whether it’s a family relationship, whether it’s a friendship, whether it’s the warmth and empathy and this sort of bravery to stand up against something you don’t believe in. All that we still think can provide hope and positivity to the audience.

But that doesn’t mean that the challenges are not real. It’s through those shared challenges that people empathize with our characters.

© 2023 Chimney Town

I think that really shines through in Bottle George. In my interpretation of it, and please push back if I’m totally off base, George in the bottle versus George outside of it are the best and worst versions of this person.

TSUTSUMI: Exactly. Those exist simultaneously, and oftentimes, the worst and best versions of yourself don’t see eye to eye. You don’t know when you become that worst version of yourself, and you almost see it as if that’s a horrible person. Only to realize that’s you.

That’s something that we wanted to convey. The huge issue with addiction is you don’t know that you’re addicted. That’s the most challenging part of it now.

Now that we’re talking more about Bottle George, what first attracted you to the Bottle George project? Were you already familiar with Akihiro Nishino‘s other work?

TSUTSUMI: Yes!

Akihiro is a very unique talent. He’s a comedian, author, and celebrity; he comes from a group of people that I don’t normally interact with. He lives in the world of celebrities, and I live more in production. Like, you just stay home and do the work in the animation world. But he started creating stories, animation, and kids’ books. He’s a pretty fascinating guy! So we had one occasion where we had a talk event, and I didn’t know much about him other than the fact that he’s a famous guy. We hit it off really well from the start. And he said, “Let’s start this project together!” So, my attraction to this project started with him, not with the idea.

And oftentimes, I feel like when people collaborate, and this is certainly true for me, you collaborate with people you want to work with, not only on an idea you like. I think an idea is important, but I think you’re committing to this new project, this new collaboration, based on the people you want to interact with. And he was that person! I thought it was really interesting. He had this really out-of-the-box idea, and that’s how we started. He had this idea for a short film immediately after we said, “Hey, let’s do something together.”

The next day, he submitted this story of Bottle George, and I thought, “Wow, that’s really cool!” At the time, the story was very different, but the concept of the character stuck in the bottle was there and amazing. It really sparked inspiration in me.

It took a few years to get to our final story because we got swamped while on this production. But really, he’s one of those guys who is not all talk. He actually follows up with action. And I immediately felt like, “This guy’s real.”

I had to respond. We had a lot of back and forth, and I proposed bringing dwarf studio into the picture. That was my long-time dream outside this whole thing; these three parties came together, and this project started.

That actually ties well into a follow-up question. Bottle George is your second time working with the dwarf studio, correct? How did that relationship come about?

TSUTSUMI: The first time was more of, hopefully, mutual admiration. I admired dwarf from afar for a long time. We tried to collaborate on Oni: Thunder God’s Tale, the series project I did. It was supposed to be a full-on stop-motion project. We did a pilot together, and it didn’t end up being a stop-motion in the end because of various reasons. And I was very unhappy about it. I mean, I’m happy with the final product. The CG was wonderful. But it’s more like I was so disappointed I couldn’t work with Noriko [Matsumoto]-san. I couldn’t work with the team at dwarf. I really fell in love when I worked with them the first time. So when this project became a reality, I pitched to Akihiro, “What if we bring studio dwarf into the picture? I think you will love it.”

Does utilizing stop-motion animation bring unexpected challenges or benefits to Bottle George as a project? I’d love to hear about your experience working in this art form.

TSUTSUMI: I’m going to give you two answers.

One answer is being able to step back and really think about why I love the experience of working on Bottle George, and it’s because of the people. It wasn’t necessarily because it’s stop-motion, but because I got to work with people from dwarf, and they work in the stop-motion medium.

They are just incredible craftsmen, incredible artists, incredibly smart people! Takana is a production manager. You have to be so organized to do stop-motion because you cannot reshoot like you can in CG or hand-drawn [animation]. In those art forms, you can go back into the frame and fix the frame. You cannot do that in stop-motion. So, there is a lot of planning and creativity involved.

I guarantee these guys would be just as successful if they worked in CG or 2D animation. I think it’s the people. So that’s the bigger answer. Of course, the medium of stop-motion did cause challenges and benefits not present in a medium like CG animation.

One of the most difficult things about stop-motion animation is that it can turn into a puppet show very easily. And there’s nothing wrong with a puppet show! I think puppet shows are beautiful, fun, and cute, and that’s all great, but maybe not in a movie about addiction and family. I didn’t want this to become a puppet show. I think this needed to be something that people could really believe is a real thing. It’s a real story, a real emotion. I challenged them, and I think the dwarf team came back through with the crafts and incredible artistry. I hope audiences don’t forget it’s stop motion, not CG. Like some people today [at the screening] thought it was maybe CG in parts.

And I told them, no, it was full stop motion. They were like, “What?” They couldn’t believe it. That’s a huge compliment.

© Chimney Town

Building on that, what considerations need to be made when designing a character for stop motion? Are there multiple models of characters like Chako?

TSUTSUMI: Yes! We have three models, three puppets of Chako.

In terms of character design, yes, there’s a huge requirement. And what I love, again, what I love about the dwarf team, [is that] they actually said to me, “Hey, don’t worry too much about what the limitation of stop motion is. We’ll tell you if it’s impossible, but tell us what you want because we’d love to make this. We’d love to do something we’ve never been able to do before.”

It’s like, who says that, right? What kind of producer would say that? And I appreciated that because even if dwarf has been doing this for 20 years, they’re still upping their game and reinventing themselves. That’s why I love working with dwarf.

I feel like they have the spirit of a rookie, of a young, innovative studio. And I love to see that! Tonko House wants to be like that.

Okay. I think the only big question I have left is, have you ever felt any pressure creatively as a result of your familial connection to Hayao Miyazaki?

TSUTSUMI: Oh, well, maybe not pressure, but there is something.

Animation filmmakers, especially from Japan, but I think now all over the world, have all been influenced by Hayao Miyazaki. I’ve been heavily influenced by his work and I think it’s impossible to try to do something he’s done. It’s just impossible.

And the only thing we can do is to learn from him. I still sometimes try to analyze myself. I ask, “Why am I so attracted to his movies?” And every single movie is different. The latest one I was just so attached to, but not everybody liked that movie [The Boy and the Heron]. You know, it’s kind of controversial.

But I have a really strong connection to that film, and I’m still, to this day, trying to analyze it. And I don’t think he’s the kind of a filmmaker who does what Disney does or what Pixar does. Like, you know, there’s no textbook for Hayao Miyazaki or how to become Hayao Miyazaki.

That’s why I think he’s special, and that’s why I think nobody can be Miyazaki. You know, a lot of people say, “Oh, this director is the next Miyazaki.”

Nobody. No one can do it even if they try to. So for me, the pressure is definitely not felt at all. Of course, I have a distant relationship with him, but for me, he’s still my hero. He is still someone I admire, and if he ever makes anything, I would just go out of my way to watch it because his films are incredible.

It’s tricky because he is, to many people, the introduction to animation as a medium. But then also, as you were saying, The Boy and the Heron was very clearly about his 50-something-year-old career in this art form and the baggage that comes with that, the legacy that comes with that.

TSUTSUMI: Of course. I think someone who, you know, all of us would love to follow this career, to relate to the movie differently. In a simple way, I watched The Boy and the Heron as his emotional relationship with his mother. Then, I also understood that it was so much of a parallel to his career and the death of Takahata that I was blown away. And now I’ve watched a movie so many times. So many different lenses, and every single one is so interesting. At the end of the day, I think we all love him as a person, not just his movies. We love to find out anything about him as a person. He’s an amazing human being. Maybe not the most perfect or nice, but he’s just an attractive person everybody wants to hear anything about.

He’s magnetic.

TSUTSUMI: Yeah, he’s very magnetic.

Thank you so much. That is everything I came prepared with. Is there anything you want to let people know about Bottle George? What might you be working on next?

TSUTSUMI: It’s been a dream to work at Tonko House and with dwarf. Hopefully, this will be the first step towards doing something bigger. I really think in today’s day and age, with AI’s introduction to the medium of animation, stop-motion could be an interesting section of the medium. How and when is AI going to influence the animation medium? I’m not sure, but I have a strong feeling stop-motion is going to come back very strongly in the next few years, and I look to dwarf to bring that medium to the world. With the proof that [stop-motion] could be mainstream once again, and hopefully, it’s not just a passion project.

I’m sorry. That merits a follow-up question. Do you see AI as being constructive to the stop-motion animation process, or do you see stop-motion animation becoming more popular as AI becomes more common in other forms of animation?

TSUTSUMI: That latter, but I think that AI might, well, definitely will, help the process of stop-motion for sure. But the fact that people make [stop-motion] with a tactile process, I think that would be the last thing to go in competition with AI.

Everything has to be more considered, reshoots are a lot harder, and you can’t really cut corners with stop motion.

TSUTSUMI: Yes, it’s very hard to cut corners in stop motion.

Fantastic, thank you so much for this interview!

TSUTSUMI: Thank you, I really appreciate it.

The San Francisco Int’l Film Festival hosted the world premiere of Bottle George on April 27. The creators are currently planning to bring the film to more festivals in Japan and abroad in the future.

Source link

#Beauty #StopMotion #Animation #Bottle #George #Director #Daisuke #Dice #Tsutsumi